Duke Riley at MagnanMetz Gallery

I’ve become a big fan of Duke Riley’s work. Riley combines historical research, public intervention and skilled craft to generate narratives that are immediately engaging and subtly layered and complex.

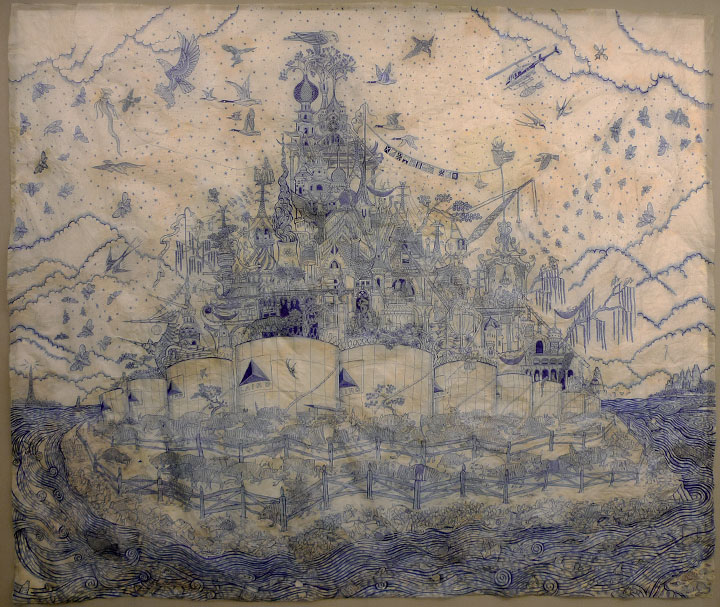

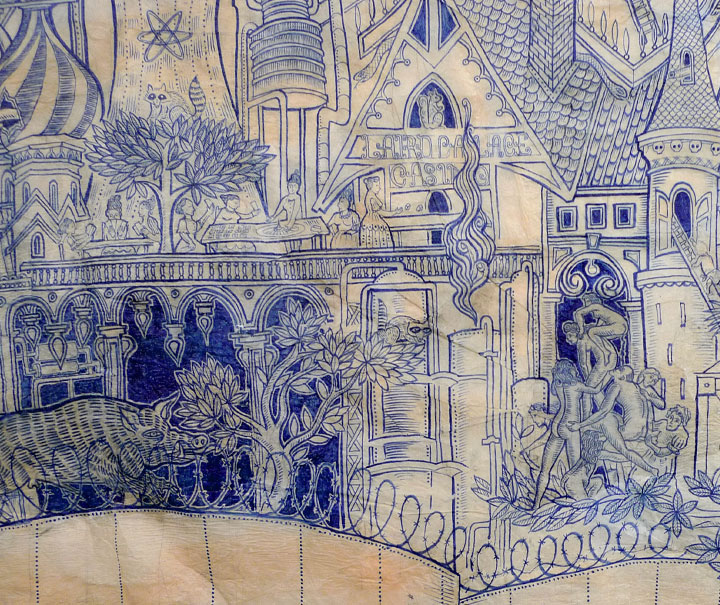

I Photoshopped the drawings pictured in this post in order to better see the detail that Riley executes in his graphic work; they are worth seeing in person whenever possible. Although the only work documented in this post is graphic representation, Riley works across media and he has gotten the most attention for his public interventions, such as “After the Battle of Broolyn” for which he built a replica of an 18th Century U.S. Revolutionary submarine “The Turtle” and set out on the Hudson to attack a ship, the Queen Mary 2 docked off Manhattan. The NYC Coast Guard hauled Riley and his submarine from the Hudson.

The latest exhibition presents two installations revolving around two separate historical narratives – the hobbo ballad “An Invitation to Lubberland” and Petty’s Island, a Citgo owned island in the Delaware River.

I didn’t have the patience to watch the videos portraying An Invitation to Lubberland which presented a late 19th century/ early 20th century dressed man running around underground tunnels. I was much more drawn to the second work presented “Reclaiming the Lost Kingdom of Laird” which consists of an intervention upon a Citgo fuel storage tank and a reclaiming of the island by the Laird Kingdom Liberation Army that published a letter to Hugo Chavez on the Huffington Post reclaiming Petty’s Island.

The project includes a giant portrait of Ralston Laird painted onto the top of a storage tank, interviews with the great great grandson of Ralston Laird, artifacts of the Laird family and beautiful drawings that re-imagine the island. (Ralston Laird was an Irish immigrant who once lived on Petty’s Island and claimed himself king of Petty’s Island.) Below are a few closeups of the large scale drawing pictured above.

Duke Riley goes all out with his work. He ventures across boundaries to realize work that must be taken seriously due to the earnestness of execution. My only point of critique is that his graphic work is consistently in line with hipster subculture aesthetics informed by past eras of Americana and I would much rather see Riley establish his own visual language. Although the visual styles are generally informed by the era of the topic that he tackles it seems to be the same early 19th century U.S. graphic style that he recreates. Perhaps what I enjoy the most is that Riley really seems to enjoy his work thus the research leading to dense narratives that are conceptually and visually engaging.