Archive for the ‘Sculpture’ Category

Question of Intelligence

Before COVID-19 shutdown New York City, I had the opportunity to experience the exhibition “The Question of Intelligence – AI and the Future of Humanity” curated by Christiane Paul at Parson’s Kellen Gallery. I did not enter the exhibition expecting to witness disparate algorithms animating the exhibition space. It took me a few minutes to realize that the empty gallery (populated only by myself and two silent gallery sitters busily working, I suppose, on their school work) was brought to life by artworks forced to listen to one another and respond. I’m talking about artworks sensing via microphones, cameras, the internet; processing through artificial intelligence, machine learning, algorithms; and communicating via speakers, projectors, screens, printers, the internet and miniature swamps.

Christiane Paul has assembled elder artificial intelligence artworks over 40 years old (though still learning) with nascent works just starting to realize themselves. With the popular explosion of catch phrases including “Big Data,” “AI,” “Machine Learning,” “Today, right now, you have more power at your finger tips than entire generations that came before you…” (I used to appreciate Common before the Microsoft commercial, now I cringe when I hear his voice), Paul has curated a learning experience that recognizes the generational history of artificial intelligence as a creative medium.

Upon entering the gallery, one hears female artificial voices generating poetry or relating temperatures and soil humidity and other environmental measures or in the distance an occasional tweet. To the left, I saw a big black microphone and elected to approach it as the first means toward interactivity. I introduced myself and then watched my words projected onto the wall along with Chinese-style landscape paintings. Trails are drawn from word groupings to word groupings along with drawn landscapes and icons forming a word and image map. The projection is a mind map generator based on the words captured by the microphone. Following a few phrases, I decided it wasn’t very interesting and decided to move on. Adjacent to it is Lynn Hershman Leeson’s chatbot Agent Ruby (2001), but having interacted with one of Leeson’s works at Yerba Buena’s “The Body Electric” recently, I only spent a minute with it before moving on, also it didn’t know what to make of what I was telling it.

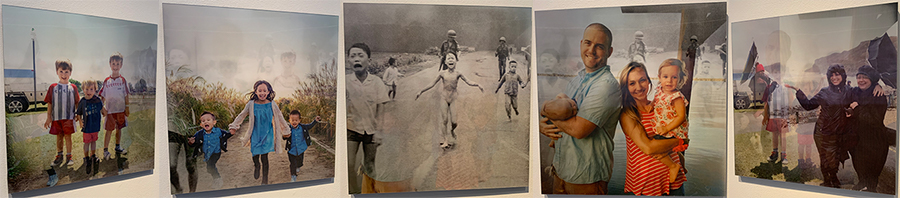

Adjacent to the chatbot, is Lior Zalmanson’s “image may contain” in which the artist feeds historically significant images into FaceBook’s Automatic Alternative Text image recognition algorithm, an accessibility AI to help contextualize images for the blind and sight impaired. The artists uses the uncontextualized and minimal description of the historical images to identify “similar” images and then collapses them onto lenticular prints. Above are the images that appear in the first print as I move from left to right. The work simply and clearly shows that bots such as AAT should not be used to present information and least of all pretend to be a source of knowledge, at least not yet.

Similarly, Mimi Onuoha uploaded a photo of her mother “to Google’s reverse image search, which allows one to upload a picture to find online images that the Google algorithms identify as related.” Scaled, printed and framed from the initial image at the center to the algorithmically related images encircling, a seemingly family home portrait wall appears, leading one to question the process of algorithmic categorization based entirely on visual similarity. With such a project, I can’t help but recall eugenics and Sekula’s “The Body and the Archive.”

I then circled back toward the center of the gallery to try and figure out what was going on with “The Giver of Names” by David Rokeby. And it wasn’t until I read the instructions and changed the objects on the pedestal to assemble my own still life that the brilliance of the exhibition really dawned on me!

“The Giver of Names” (naming since 1990) consists of a monitor, speaker, old CCTV camera, pedestal, pile of old toys and a program that tries to understand what it is seeing through the camera to generate poetry. Once I removed the toys left on the pedestal and placed my own selection, I watched the AI go into action by identifying shapes and colors and then trying to make sense of what it was identifying or “seeing.” Those shapes and colors feed a poetry algorithm that speaks and writes to the monitor adjacent to the CCTV camera. Meanwhile, just beyond this installation, the not very interesting mind mapping microphone is also capturing this generated poetry as it echoes across the gallery and starts mind mapping away. AWESOME! The gallery is its own loop of machines churning away at one another’s utterances. This realization helped me refocus my attention and expand my time with each work. I tried to capture this in the video at the top of this entry.

Near the entrance on a wall monitor, hangs AARON which I had merely paused at for a few seconds but now returned to observe. “AARON is the earliest artificial intelligence program for artmaking and one of the longest running ongoing projects in contemporary art. Harold Cohen started creating AARON at UCSD in the late 1960s and developed the software until his death in 2016. In this video AARON produces a new color image every 10 to 15 minutes.” As one tours the gallery, AARON is quietly working away creating shapes and lines of color, artful abstractions.

Back near the center of the gallery, just beyond “The Giver of Names” is another work with a female computer voice speaking at intervals. Tega Brain’s “Deep Swamp” asks “if new ‘wilderness’ is the absence of explicit human intervention, what would it mean to have autonomous computational systems sustain wild places?” The handsome installation has three AIs, Nicholas, Hans and Harrison each “engineer their environment for different goals. Harrison aims for a natural looking wetland, Hans is trying to produce a work of art and Nicholas simply wants attention.”

“Learning to See” by Memo Akten uses machine learning to relate the objects on a pedestal that a camera captures to five different data sets that the system has been fed. The visitor can re-arrange the objects on the pedestal to see new interpretations. Across from the pedestal on a wall is a split screen that shows the image captured by the camera adjacent to the system’s interpretation. “Every 30 seconds the scene changes between different networks trained on five different datasets: ocean and waves, clouds and sky, fire and flowers, and images from the Hubble Space telescope.

Similarly across the gallery, hang a series of prints by Mary Flanagan. The work is [Grace:AI] in which generative algorithms trained on thousands of paintings and drawings by women to create a series of images. “[Grace:AI] was tasked to create her ‘origin story’ by looking at 20,000 online images of Frankenstein’s monster and producing its portrait.”

Both “Learning to See” and “[Grace:AI]” employ generative adversarial networks (GAN), to generate new visualizations. Using GAN anyone can put their own conceptual spin to generate a data set for the machine to learn and see what it spits out. Over the last few years, I’ve seen a few similar projects, my favorite remains an early one – the MEOW Generator trained on a cat dataset.

Perhaps the most darkly monumental project are the large four black machines with spinning fans, exuding steam and ticker tape – the installation component of #BitSoil Tax by LarbitsSisters. The project proposes the fair redistribution of internet wealth to all people through a new taxation system. The installation is utopian, dark and whimsical.

Other projects on exhibit include “Futures of Work” by Brett Wallace, and Ken Goldberg and the AlphaGarden Collective.

Calder & Oiticica at Whitney Museum

If you enjoy work that breaks the norms of fine art; work that invites the viewer to participate, this is a great time to visit the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Through the remainder of the month, on the 8th floor, one may see Museum employees activate Alexander Calder sculptures. With slight touches and hand gestures, Calder’s work is set in motion as it was meant to be enjoyed. Several pieces on display are motorized, unfortunately they do not appear to be plugged in or at least when I was there I did not see them in motion. However, the ones that are activated by human touch are beautiful to see in motion. One may immediately capture the great care that Calder took in combining form and weight to create compositions that have expression through movement. The works are simple and delicate but when they are put in motion they appear to have their own life due to the joints and careful balancing of the pieces assembled to make the whole.

Work your way down the museum and I believe that it is on the sixth floor that one will encounter “An Incomplete History of Protest”. As problematic as the labels “Protest Art” or “Political Art” may be, many of the works in the exhibition were not made in the studio for the gallery, but were realized through collaboration and enjoyed public manifestation on the street in the midst of protest. I tend to consider such art as genuinely “political art” or “activist art”. The exhibition does a reasonable job of presenting an overview of such work over the last fifty years in the United States.

Further down the building, perhaps on the fifth floor is “Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium” which to me is the most fun of all the exhibitions on view. It is unfortunate that the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica died at 42 as he was prolific and realized work that is at once provocative, social and contemplative. Several of the galleries, allow the viewer to walk through the work or even wear the pieces as Hélio Oiticica meant the work to be! This is great as it is not uncommon for work originally designed to be tactile has been removed from the visitor’s reach, not so with Oiticica’s exhibition. One gallery even features clothing designed by Oiticica hanging on a rack, for visitors to try on and model in front of a mirror. A walk through the installation “Tropicália, 1966–67” alone is worth the trip to the Whitney. As one winds through the installation, visit the two large parrots in a white cage and if you go around 3pm when they are fed by their handlers you will enjoy their sounds resonating throughout the exhibition.